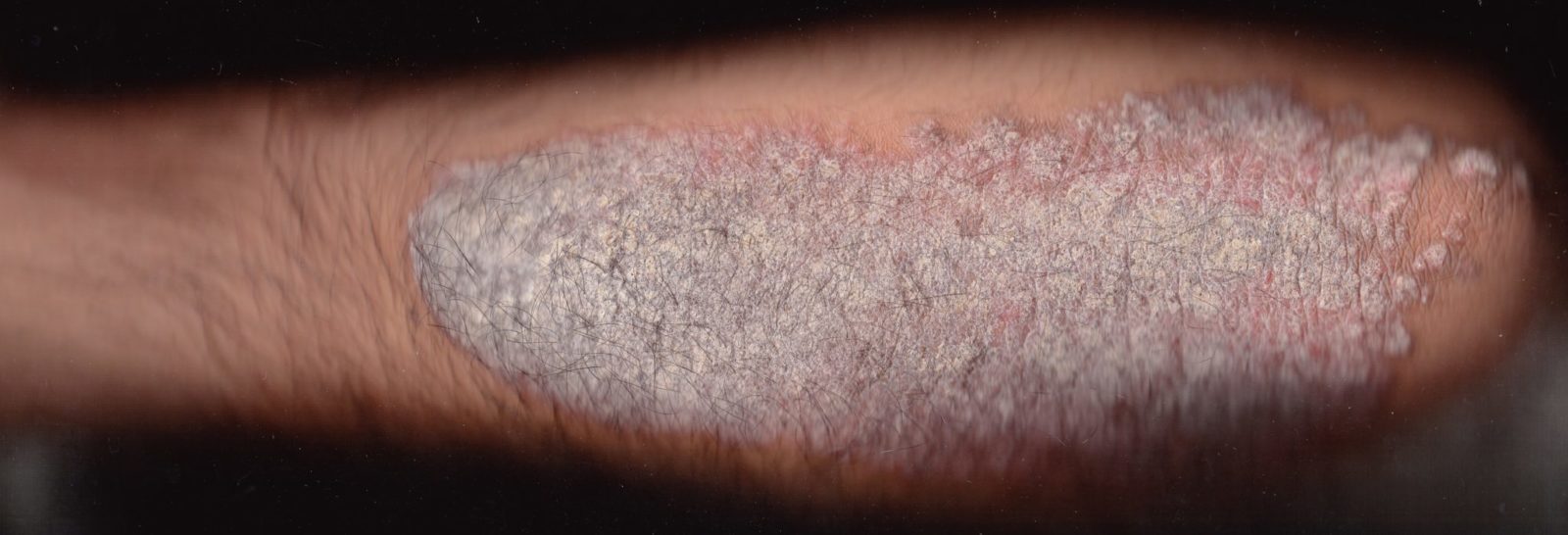

Psoriasis. Is this caused or exacerbated by stress?

Psychodermatology has emerged as a new subspecialty of dermatology and psychiatry. It even has its own organization, the Association for Psychoneurocutaneous Medicine of North America. On their website you can locate a psychodermatologist in your area.

What exactly is psychodermatology? According to a review article in American Family Physician “A psychodermatologic disorder is a condition that involves an interaction between the mind and the skin.” They break it down into three categories:

- Psychophysiologic disorders that become worse with emotional stress, like psoriasis and eczema

- Primary psychiatric disorders that result in self-induced cutaneous manifestations like trichotillomania and delusions of parasitosis

- Secondary psychiatric disorders where disfiguring skin disorders result in psychological problems such as decreased self-esteem, depression, or social phobia

They stress the importance of understanding the psychosocial, familial, and occupational context of skin disease. Yes, mainstream medicine is “holistic,” addressing everything about a patient that might affect diagnosis or treatment. This is true holistic medicine, not the kind of thing alternative medicine talks about.

Secondary psychiatric disorders

This is kind of a “well, duh!” thing. It goes without saying that if someone has a disfiguring skin disease it will have a psychological impact on his life in one way or another.

Primary psychiatric disorders

In addition to trichotillomania and delusions of parasitosis, there is dermatitis artefacta, where skin lesions are produced by the patient’s own actions. It’s also known as neurotic excoriations. It can be a form of emotional release in situations of distress. Patients will often deny scratching, but if they are prevented from touching the affected area (for instance, by a cast that covers a lesion on the arm) the lesion will heal.

Anecdote alert! I can’t vouch for this, but I heard it from the girlfriend of a dermatologist who told her about one of his patients. The patient had a skin lesion on his arm that he perpetuated by scratching. The dermatologist hypnotized him and gave him the post-hypnotic suggestion that whenever he felt the urge to scratch, he would resist the impulse and instead drop whatever he happened to be holding in his hand at the moment. At the dinner table, his wife would frequently say things that annoyed him, and he would respond to the stress by scratching. When he started dropping things instead of scratching, the wife stopped saying things that made him drop his fork or his drinking glass and make a mess on the table. She didn’t consciously realize what was happening, but she had become conditioned like Pavlov’s dogs. The man’s skin lesion was cured, and so was the wife’s nagging! If it’s not a true story, it should be.

Psychophysiologic disorders

No one would deny that a person’s psychological state can affect the skin. We blush when we are embarrassed or ashamed. Our hands sweat when we are anxious, afraid, in pain, or under stress. Strong emotions can produce goose bumps.

Stress is widely believed to cause or exacerbate a great many skin conditions, from psoriasis to alopecia areata. There are plausible physiological mechanisms; for instance, stress has been shown to affect skin permeability and the antimicrobial properties of the epidermal barrier. The role of stress is supported by numerous case reports and studies that not only show a correlation but sometimes report the success of psychotherapeutic interventions.

But there is a big problem with the research. In a 2013 article in Clinics in Dermatology, Orion and Wolf say “Although many data have been published, it appears that not enough good statistical evidence exists to support them.” It is difficult to measure stress; it is usually assessed retrospectively by self-reports on questionnaires. And patients may not be aware of stresses: in a study of alopecia areata in children, alopecia patients were more likely to be a member of a single-parent family and to perceive less expressiveness within their family than epileptic patients or healthy children, but they didn’t report more anxiety or depression.

It seems clear that stress can cause or exacerbate some skin disorders. What’s not so clear is what we can do about it. As Orion and Wolf went on to say:

Surprisingly, it appears that researchers show more enthusiasm in proving psychological difficulties to be an etiologic factor in the onset, exacerbation, or reoccurrence of skin diseases, but much less enthusiasm in finding whether psychological therapies can ameliorate them…To date, we still do not know enough about how to deal with this issue, although ironically this is the most important and practical question.

Conclusion: Do we really need this specialty?

I’m all in favor of raising awareness of the possible impact of stress and psychological factors on skin disorders. But do we really need a separate subspecialty to do that? I also found references to psychogynecology, psychopediatrics, psychocardiology, psychoorthopedics, psychourology, and psychoophthalmology. Do we need a “psycho-something” for every single branch and twig of medicine? I would argue that we don’t really need such terms because good clinical medicine already has a holistic approach that takes psychology into consideration. In an ideal world, when we said “dermatology” it would be understood that we include all the psychological, social, environmental and other factors that have a bearing on the diagnosis and treatment of skin diseases.